Radicalism and Cultural Revivalism

In recent years, radicalised Tuareg groups have emerged; the most prominent example being

the northern Mali-based group Ansar Dine, which combines Tuareg militancy with jihadism. Its

leader, Iyad Ag Ghaly, fought in the Tuareg rebellions, eventually diverging from the rebels’

secular ethnic struggle to foment a religious one. Now considered a radical Salafist, Ag Ghaly

rejects many of his kinsmen’s traditions, including the use of the Tamasheq language, claiming

them to be remnants of a pre-Islamic pagan past.

Ansar Dine represents a paradox. While latching onto Tuareg cultural revivalism and ethnically

motivated separatism to build support, the group has sought to suppress Tuareg identity in

favour of radical Salafist ideas. Diverging ideologies, overlaid with existing grievances, illustrate

the dynamics that challenge a uniform understanding of the Tuareg experience.

Not long after leaving Libya following Qaddafi’s downfall, many Ishumar returned to join

their kin in the fight for control of the south.

In 2014, not long after leaving Libya following Qaddafi’s downfall, many Ishumar returned to join

their kin in the fight for control of the south. The Tuareg’s main rivals, the Tebu, are an ethnic

group native to southern Libya and Chad. While the Tuareg were celebrated under Qaddafi as

“the lions and eagles of the desert”, the Tebu were denied citizenship, education, and

healthcare.

A long-standing settlement between the two groups over territory and smuggling routes

collapsed with the fall of the Qaddafi regime. Already pitted against each other during the

revolution, tensions only escalated in its aftermath, eventually resulting in a Tuareg-Tebu ethnic

war. Home to both Tuareg and Tebu populations, and a gateway to the smuggling routes

leading towards Algeria and southwards into Chad, the city of Ubari became the main

battleground.

Many of the Tuareg forces in Ubari belong to Katiba 315, one of the main Tuareg militias of the

south and loyal to the government of Tripoli. The group was founded by Ahmed Al Ansari, a

Salafist Tuareg and former Libyan army officer.

Katiba 315’s Islamist affiliations provided an opportunity for rivals to paint the Tuareg as

jihadists, both delegitimising their cause and politicising their identity. Once thought of as largely

confined to Mali, Tuareg jihadism is now seen as a transnational problem, where militancy and

smuggling are intertwined.

The south is rich in both oil and water, and is the gateway to key smuggling routes in the wider

Sahara. The fight in the south, therefore, carries more weight than that of an ethnic feud. The

revolutionary aftermath placed the Tuareg-Tebu battle in the larger context of the Libyan civil

war between the rival governments of Bayda and Tripoli, which backed the Tebu and Tuareg,

respectively. The place of the Tuareg, and indeed other ethnic groups in today’s Libya, is being

redefined by the fighting.

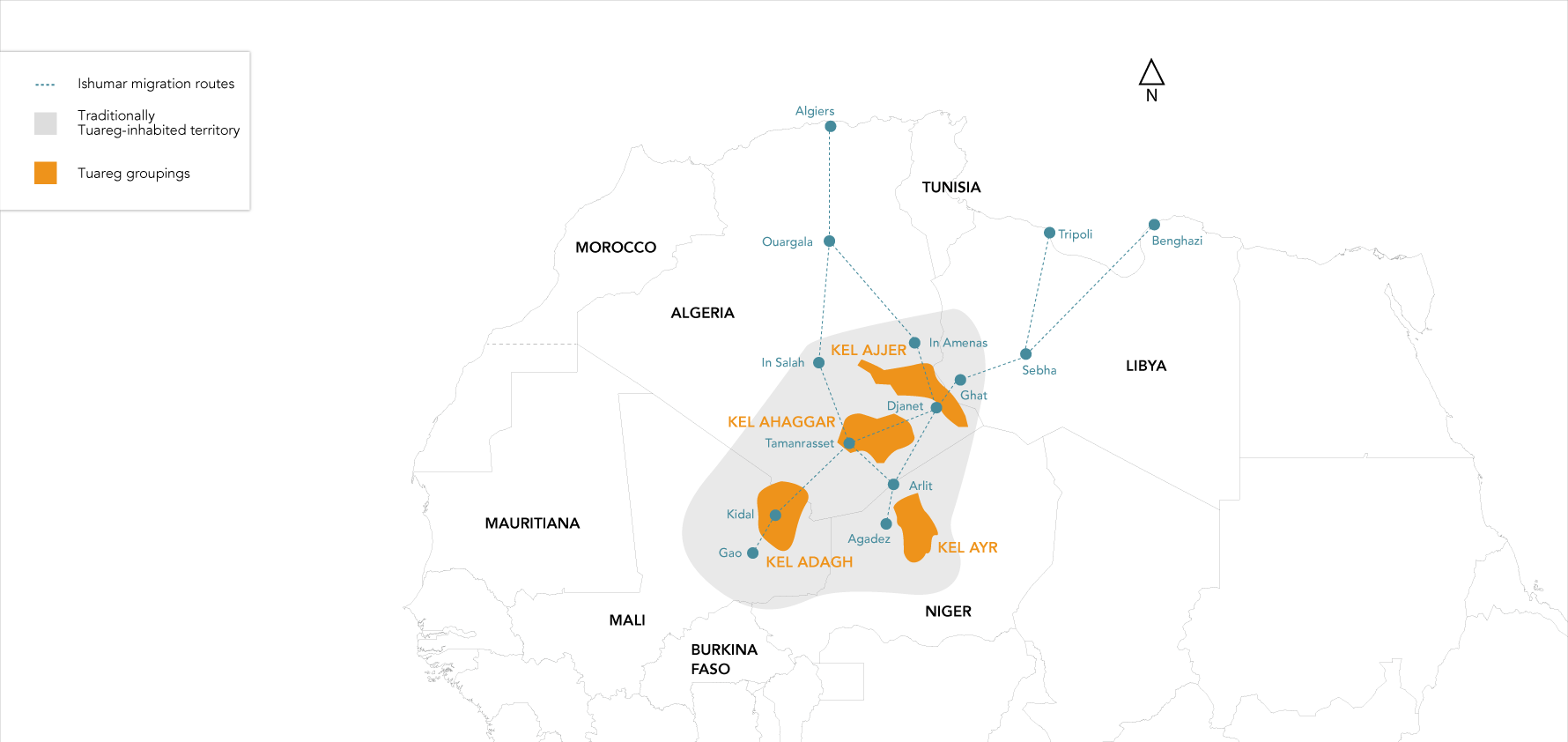

The case of the Tuareg illustrates the complexities introduced by modern borders, cutting up a

desert that once formed a single space into states embroiled in conflict and rivalry. Buffeted by

decades of geopolitical waves, they are caught between adjusting to ever-changing realities,

and aspiring to cohesion. Adding to entrenched economic displacement, the rising militant

problem in Tuareg lands has led to questions about whether the vast borderlands between the

Sahara and the Maghreb are, in fact, governed areas or spaces escaping state control.